- chapter 3 Body

- section 3.1 Body as a physical thing

- box 3.1 Assistive technology

- section 3.2 Size and speed

- box 3.2 Just walk

- section 3.3 The networked body

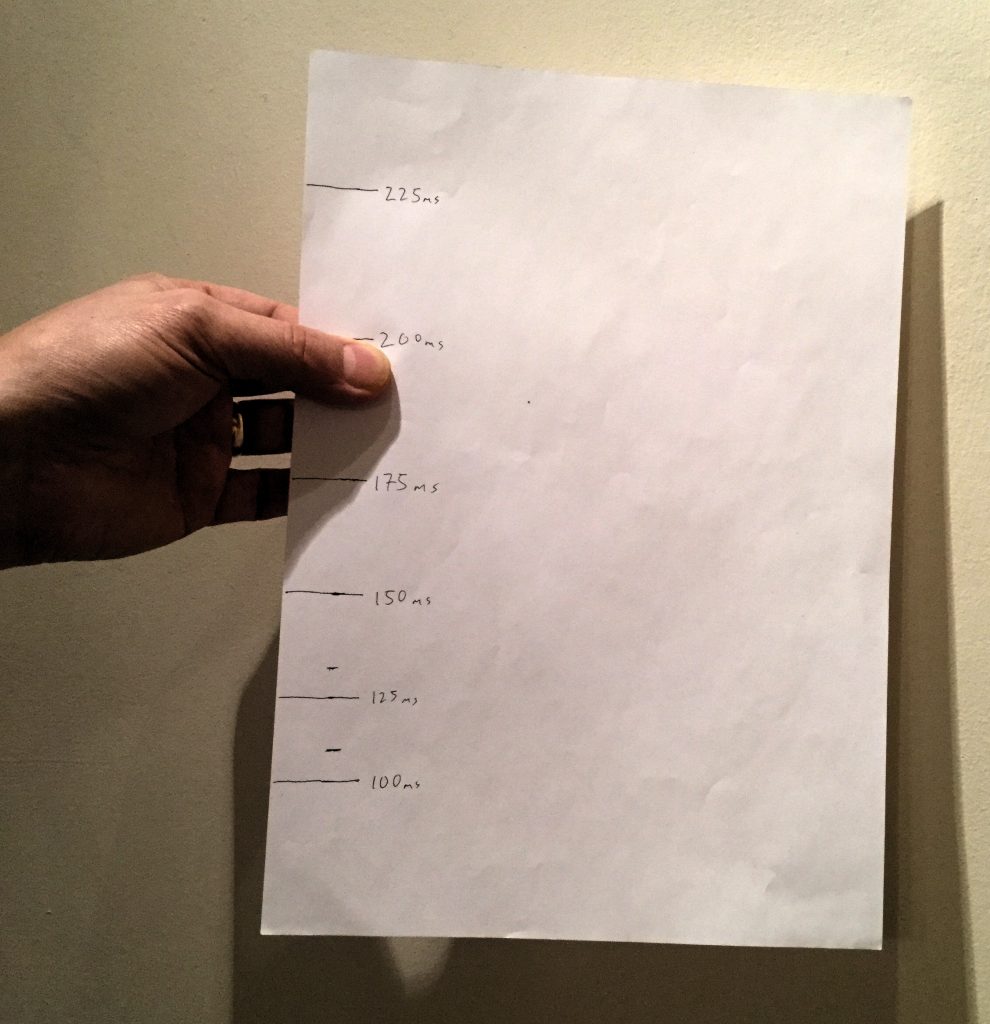

- box 3.3 How quick are you?

- section 3.4 Adapting IT to the body

- figure 3.1 Using a homunculus to design furniture

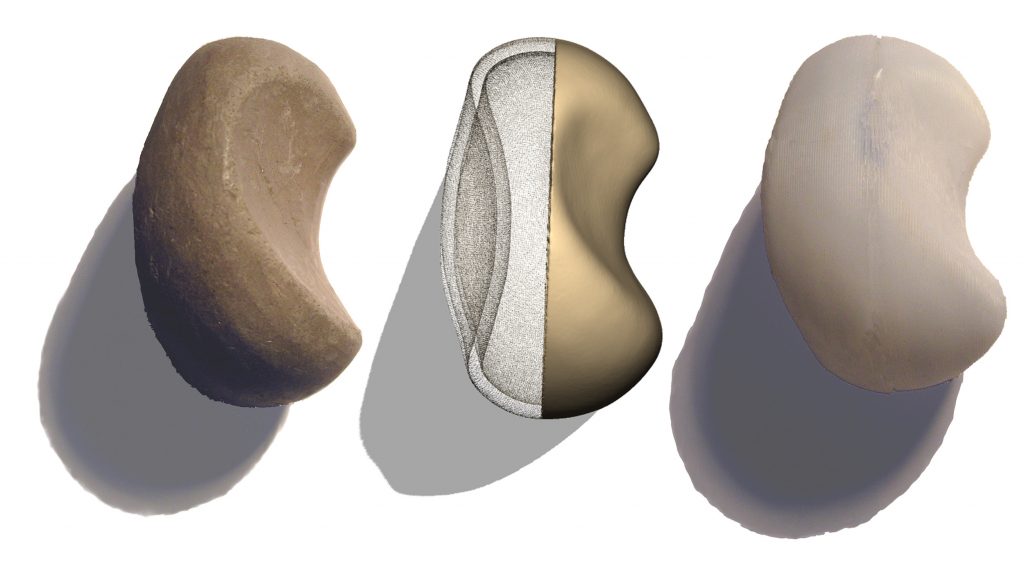

- figure 3.2 Stone-like shape moulded in clay naturally fits the hand; then transformed from clay to CAD and from CAD to 3D printed resin.

- section 3.5 The body as interface

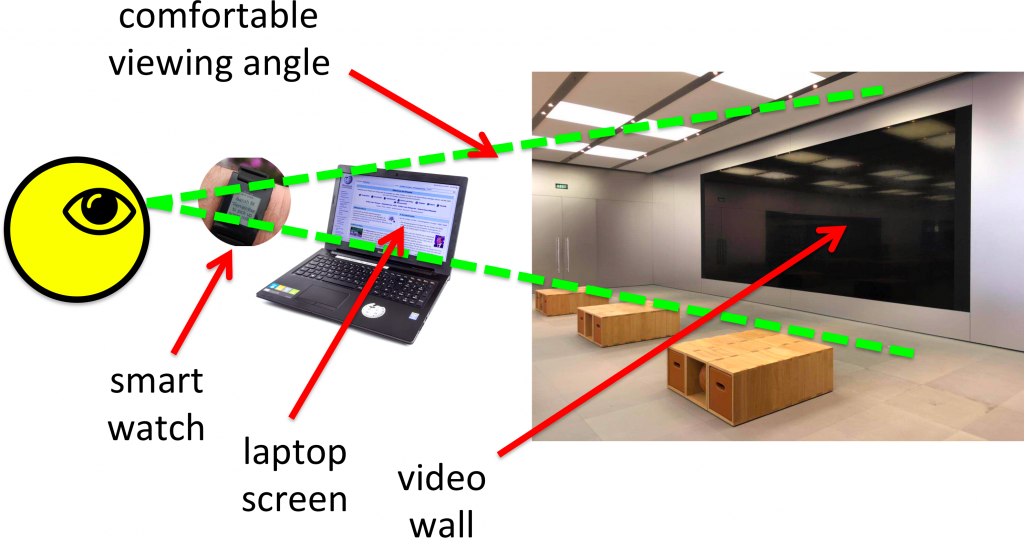

- figure 3.3 Comfortable viewing angle — closer devices can be smaller

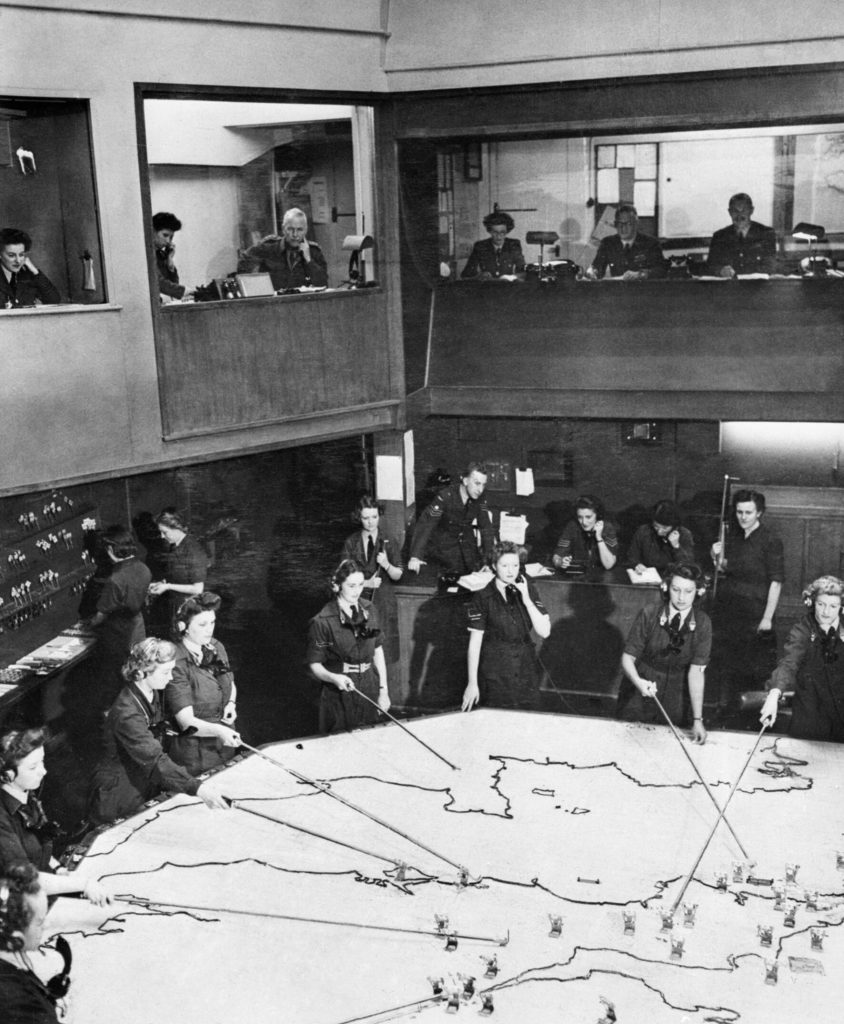

- figure 3.4 The Operations Room at RAF Fighter Command’s No. 10 Group Headquarters, Rudloe Manor (RAF Box), Wiltshire, showing WAAF plotters and duty officers at work, 1943. Imperial War Museums (image CH 11887)

- section 3.6 As carrier of IT — the regular cyborg

3.1 Body as a physical thing

Our bodies are clearly physical things, skin and bone, muscle and tendon. Some of our physiology can be understood in terms of the physics or engineering of the body. Muscles in our upper arms operate on the lower arms using pivots (joints) and levers. When we run fast our muscles need more oxygen, so we breath faster and deeper in order to get more air and our heart beats faster to distribute oxygen.

We have limits on how far and fast we can reach, how accurately we can point, how strongly we can grasp. Sometimes we do not notice the limits of our own bodies as we surround ourselves with chairs of the right height, steps that are not too steep, objects that we can lift (limited by health and safety regulations). However, if we step beyond the bounds of our constructed environment, to climb a mountain or swim in the sea, our limitations are brought sharply home to us. We work within them or perish. Even in the safe environment of our home, it only takes a small muscle strain to realise how complicated everyday actions are, how many movements we make for the simplest task.

For the elderly, or those with physical disabilities, these complications are ever present and often require special aids, from electric stair lifts to rubber cloths for opening jars. However, it is not only the elderly and infirm who use technology to go beyond the limits of their own bodies. When you drive a car, ride a lift, or even press the button on a TV remote, you are substituting mechanical, electrical or digital means for simply walking. A forklift truck helps you to lift more, a mobile phone helps you talk over distance, and a spreadsheet helps with calculation.

Box 3.1 Assistive technology

Assistive technology in the home has tended in the past to be relatively low-tech, but that is changing with automatic windows and doors operated by remote control, and sensors carried on the person or in the environment triggering alarms for relatives or carers. For example, video cameras can be programmed to learn normal movement patterns and so detect unusual activity, perhaps after a fall.

This technology is often installed with the promise of greater independence, especially important when most western countries face an ageing population and potential ‘demographic timebomb’. Allowing people to live longer in their own homes, or in specially designed independent living units, can improve quality of life and reduce demands on human services. However, the impact can often mean reduced face-to-face contact with real humans and for those under the surveillance of motion detectors and under the glare of automatic lights, the very technologies intended to promote independence can seem more like intrusion.

Sometimes we can use the limitations of the body as an explicit resource in design. The sweetie jar is on a high shelf to put it out of reach of a small child, and the lids of medicine bottles are designed to make them difficult for a child to open. For adults too, physical limitations can enforce constraints: in a nuclear bunker the two ‘fire’ buttons are placed too far apart for a single person to press both. In a digital world, sometimes things are just too easy, anything can happen at the press of a single button. It is easy to do things and it is easy to do things wrong; as in the nuclear bunker, we can deliberately use physical constraints to prevent errors, for example using recessed buttons to prevent accidentally pressing them. Perhaps computer keyboards could use haptic technology and have more resistance on the ‘delete’ button when you have a whole document selected, compared with just a few words?

3.2 Size and speed

The physical size of our body is crucial in determining how we can interact with the world. Birds can grip a wall and stand horizontal, but even the most practised trapeze artist, rock-climber or skier could not hold their bodies horizontally using their ankles alone.

This is because as an animal gets smaller its weight gets smaller proportional to the cube of its height and the distance of its body from the wall decreases with its leg length. Therefore the force needed to support it falls off as the height to the power of 4. So if you were half as high you would only need 1/16 of the force to hold your body horizontal, and if you were one-third of the height only 1/81 of the force. Of course, if you were smaller, your muscles would also be smaller, but the ability to exert force is determined by the cross-sectional area of the muscle, which falls with the square of your height. If you were half the size your muscles could exert 1/4 of the force, or if you were one-third of the height, 1/9 of the force — you can see that the muscle force gets smaller much more slowly than the required force, so that it gets easier and easier to support your body. This also means that bones can be smaller, and lighter, thus increasing the effect. So that bird, perhaps 1/20 of your size, finds it 400 times easier to hold itself horizontal than you do.

Our physical size also influences the speed we can move. Try this experiment. Stand up and raise one leg in the air. Hold the raised leg with the knee stiff and start to swing it back and forth — see how fast you can move it before you feel yourself losing balance. Now do the same again, but this time keep your knee loose so that your leg can ‘flap’ back and forth. Notice how much easier it is to move quickly when your knee can bend.

This, again, is basic physics. With your knee fixed your leg is a simple pendulum, like the pendulum in a grandfather clock, whereas when your leg can bend it is a compound pendulum: one pendulum (your upper leg) with another (the lower leg) joined on. Each pendulum has a natural frequency, the speed it would move back and forth if you didn’t force it with your muscles, but just let it flop. It turns out that a long stiff simple pendulum has a slower natural frequency than if it is divided into two halves as a compound pendulum. In general, it is easy to make a pendulum work at its natural frequency. Think of pushing a child on a swing: you time your pushes to coincide with the natural movement of the swing. However, one has to work harder to make a pendulum work faster or slower; try making that child swing back and forth slightly faster or slower than the swing wants you to. This is why we bend our legs as we run: the natural rhythms of this compound pendulum are faster than a straight leg.

Box 3.2 Just walk

The natural frequency of a simple pendulum is 2 π √(L/g), where L is the length of the pendulum. For our legs, the weight is relatively evenly spread, with slightly more in the upper leg muscles. So the effective length to the centre of gravity is around 30cm, giving a natural frequency of about a second.

So, the speed we can move our limbs, and hence the speed with which we walk and run, is directly related to the length of our legs (and indeed our torso and arms as they keep pace). Bridge designers have to take these natural rhythms into account and try to avoid bridges that bounce up and down with a frequency of near a second. This is also why soldiers break step when crossing bridges; all of them walking at the same speed could cause a bridge to build up a wave of motion.

The designers of the Millennium Bridge over the Thames river in London forgot that while the up-and-down pace of normal walking is about 1 second, the side-to-side pace as we swap weight from one leg to the other is twice that, around 2 seconds, or a frequency of 0.5Hz. Unfortunately the bridge had a side-to-side natural swaying frequency of precisely 0.5Hz! This would not have been so bad if not for the fact that when we are on a swaying structure we tend to fall into step with it, to keep ourselves upright, so that those walking across the bridge became rather like a single line of marching soldiers [SA05;JS15] .

In order for us to walk at around 1Hz, or one pace per second, our brains must be able to drive muscles at this kind of pace (and faster for running). This may well affect the way we can keep time. Orchestral conductors say that the slowest beat they can reliably keep is about 40 beats per minute; that is about the same frequency as a very slow walking pace. While we often think that we dance to music, it may well be that it is the other way round; our natural sense of rhythm has its origins in the length of a typical leg. We don’t dance to music, we music to dance.

3.3 The networked body

At the other end of the spectrum, the fastest speed at which a highly practised person can tap their finger is around 10 beats per second, with most of us much slower. Try it with a stopwatch. To get faster rhythms a drummer will use two hands, or a pianist several fingers. Even our tongues can’t move arbitrarily fast. Try counting out loud 1 to 10 again and again as fast as you can. Can you get an average of much faster than 5 or 6 counts per second? Here the limits are to do with the raw speed of muscles, not the combination of length and gravity in a pendulum. However, this is related to another set of physical processes in our bodies. When you want to move your hand, signals pass from your brain down your spinal column to the 5th–8th vertebrae, then along a nerve to the muscles in your arm. If you watch your hand you can see where it is, or if it touches something you can feel it touch. However, it also takes time for signals to pass from your eyes through several layers of nerves to your brain, or for the signals from the touch receptors in your hands to pass up to your brain. Altogether the round trip from sending the signal to seeing or feeling what happens takes around 150-200 milliseconds.

Box 3.3 How quick are you?

You can measure for yourself the round-trip time from eyes to muscles. Take a sheet of paper (A4 or US letter). Hold the paper at the top, and ask a friend to put their fingers close to the bottom of the sheet and be ready to catch the paper when it falls. Then let go. Mark on the paper where they caught it. Do this several times, each time they will catch it a slightly different place.

The average distance between the bottom of the paper and where they catch it tells you the total reaction time, from seeing the paper move, to actually moving their fingers. You can work this out using the speed of fall (1/2 g t2):

| reaction time | distance fallen |

|---|---|

| 100 ms | 5 cm |

| 150 ms | 11.25 cm |

| 200 ms | 20 cm |

| 250 ms | 31.25 cm |

If your friend is very canny, they may notice your fingers start to move just before they open, so you may need to cover your hand with a second piece of paper.

As an alternative test have them keep their eyes closed, but start with the paper touching one of their fingers so they can feel it begin to fall. Are they faster or slower to catch it?

Then try doing a countdown: say out loud 3, 2, 1 and then drop the paper. See how much faster they are when they can time their movement to coincide with yours, rather than waiting to see the paper fall.

These delays in your body are similar to those in a computer network and about the same as the round-trip time taken by Internet signals when you are accessing a web site in your own country (intercontinental times are more like 150-200ms in each direction). Although 200ms sounds fast, your arms can move a long distance in that time, and a fast tennis ball, baseball or cricket ball would move 8 metres. Because of this, skilled sports players work predictively, their brains working out where the ball will be when it is close to them and then ‘telling’ their arms where to move to meet the ball when it comes — there is simply not enough time to see the ball coming when it is close.

3.4 Adapting IT to the body

The importance of understanding the human body in interacting with technology pre-dates digital technology. The field of ergonomics can be traced back to the mid-19th century or even Ancient Greece [Ja57;MP99], but the modern academic field developed in the 20th century especially during the Second World War. Ergonomics originally focused on the body and physical movement: the appropriate height of a desk or a kitchen worktop, and the layout of controls in a car are all in the purview of the ergonomist, and we are used to seeing products advertised with ‘ergonomically designed’ handles or controls. However, by the early 1980s a sub-area of ‘cognitive ergonomics’ had formed, including cognitive issues alongside the physical body.

Effective ergonomic design is important for comfort and enjoyment — we all know the feeling after sitting in an uncomfortable seat during a long meeting. However, more important are the implications for health and safety. For a pregnant woman or someone with back problems, poor posture is not simply a matter of comfort. If you are reaching a long way to access the HiFi controls on a car, you may not steer a straight course or be as fast to react. For regular computer users RSI has become endemic and this has spawned a whole range of special ‘ergonomic’ keyboards, although the increasing use of laptops has made it more difficult to obtain the optimal screen and keyboard configurations.

While ergonomics was one of the foundation disciplines of human–computer interaction, it is perhaps less evident in recent years, when aesthetics of design often dominate over fit to the human body. For example, the older curvy Apple laptops had a trackpad in front of the keyboard with the ‘mouse button’ on the front edge of the computer. On later laptops, however, the button was moved next to the trackpad and on the top; later still it was integrated into the trackpad. The older design allowed the thumb to be used to squeeze the button in a natural grasping action, whereas the later designs required the thumb to press sideways and outwards, a very unnatural action. Furthermore, to avoid the thumb touching the trackpad the arm has to be held with the elbow twisted away from the body.

On the positive side, effective placement and shaping of controls can make physical tasks effortless and easy to learn. In an experiment Jo used different design tools to create several designs to the same brief [DG10]. One of the designs started out using hand-moulded clay and ended up rather like a small pebble with a depression on one side. When you pick up the ‘pebble’ it naturally falls into the right direction in your hand, without the need for instructions.

Fig. 3.2 Stone-like shape moulded in clay naturally fits the hand; then transformed from clay to CAD and from CAD to 3D printed resin.

3.5 The body as interface

Archaeologists often try to understand a society from its material remains; in this vein, more than 20 years ago Bill Buxton imagined what a visitor from another planet would infer about the human species from the evidence of a standard graphical user interface. There would of course be a single large eye (single because a normal screen does not require binocular vision), a single hand for moving the mouse and a single finger (for the Mac), or perhaps two fingers for pressing mouse buttons. There would be other fingers for typing (although most of us manage with three) and a rather limited ear for hearing the odd beep. In contrast, most musical instruments use a nearly full range of fingers, and in the case of the organ and drum-kit, also two feet.

Buxton was early in advocating the use of both hands (and sometimes other limbs) for input, but in recent years multi-finger and multi-hand interaction has started to become mainstream. The iPhone and similar devices use two-finger gestures to shift, stretch and scroll content, and large displays such as Microsoft Surface can use fingers on both hands, or indeed several people’s hands.

Touch-based devices have a natural scale determined by the size of the human body: hand contact limits one to stretches of around a yard or metre from the body for horizontal surfaces, and a little more (allowing for knee bends and arms stretching) for vertical ones. Larger displays require physical movement along the display, or some form of indirect interaction.

Effectively any display has a natural distance for viewing so that it does not take too wide or too narrow a viewing angle, typically between 20 and 45 degrees. Too wide means you have to move your head excessively with, if the display is flat, a very oblique viewing angle. Too narrow means only limited information can be displayed. There are exceptions, a wrist watch has a small display because it has to fit on your arm and correspondingly has limited display resolution. At the other extreme a virtual reality CAVE can produce 180 to 360 degree panoramas, although you need to look around to see it all fully, as peripheral vision is far less detailed than central vision.

The combination of distance and angle creates a rhomboidal space, usually from one to three screen widths wide, within which it is sensible to view the display (more details in Chapter 14). If the distance to the display is too large, interaction will normally need some sort of remote control device, for example the TV control at home or the long sticks used to move aircraft in WWII Air Force control rooms. The size of the area also determines how many people can see a display at the same time.

Fig. 3.4 The Operations Room at RAF Fighter Command’s No. 10 Group Headquarters, Rudloe Manor (RAF Box), Wiltshire, showing WAAF plotters and duty officers at work, 1943. Imperial War Museums (image CH 11887)

The body is not just used for touching and seeing. In gesture-based interfaces cameras track the position of arms and hands so that one can make gestures to control a computer system, either alone or in combination with voice commands: “put that there (points)”. Gestures can also be tracked using devices we hold, for example the Wiimote and phones with accelerometers.

GPS-enabled devices and instrumented public spaces allow a level of interaction that is governed by the movement of your body through space. With a Google map on a fixed PC you navigate through the map by using zoom and pan controls, but with a SatNav the navigation on the map is driven (literally) by the motion of the car. Proximity-based technology, such as Bluetooth, WiFi or your mobile phone cell NFC reader, also offers ways to create interaction that is either modified by the context or triggered by it (for example location specific adverts). This kind of system has clear uses in tourist guides and is also finding applications in various forms of game.

Although not very ‘interactive’, biometrics are another way in which the body is used as part of technological interactions, but for authentication rather than control. Such interactions all depend, to some extent, on the large range of individual differences between people, physical features like a fingerprint or iris scan, and skills or habits like a signature. To be useful the feature needs to be (i) different enough between people and (ii) stable enough over time that the same person can be reliably recognised. What counts as ‘enough’ depends on the situation, and depends critically on whether one is seeking (a) to verify someone is who they say they are, or (b) to locate someone or identify who they are, based on the feature.

These issues have become critical in several cases where DNA evidence is used in court. If a DNA ‘fingerprint’ is unique to one person in a million, then matching the DNA found at the crime scene with a known suspect is ample evidence. However, the UK police database contains over 5 million samples [HO09]. Matching against this would be likely to find a match by random chance and might suggest a few people to check, but would certainly not be strong evidence.

Likewise, the ‘stable enough over time’ criterion also depends on context. For example, USA border controls use biometrics to match the entry and exit points of those who visit the country; this only requires stability over weeks or months. However, stability of features over many years is essential for the use of biometric identity cards … whether or not one regards that as desirable anyway.

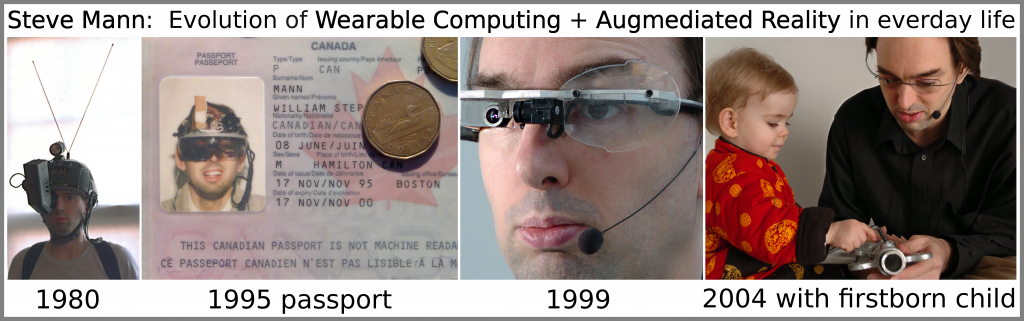

3.6 As carrier of IT — the regular cyborg

For many years some researchers in wearable computing, Steve Mann being a notable example, have conducted their daily lives with cameras strapped to their heads, screens set in eye glasses, or computers in backpacks. Over time the technology has become smaller and more discreet, but for most observers there is still something odd about these ‘cyborgs‘, who so intimately tether technology to their bodies. This disquiet was famously expressed during the alleged altercation between Mann and McDonalds staff when Mann refused to remove his digital eye glass in a Paris restaurant [Man12;Gr12].

Fig. 3.5 Steve Mann — three decades of early cyborg research

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SteveMann_30_years_of_WearableComputing_and_AR_in_everyday_life.png

But is it so unusual?

In the introduction we asked, how many computers in your house? You might also ask, how many computers on your body? Empty your pockets, bag or whatever you carry with you normally. Count the computers. You will probably have a mobile phone, USB memory stick, or maybe a smart watch. If you carry a separate camera it too will have computers even if it is a film camera; a car key with remote locking has a computer to generate unique changing key sequences. Reach into your wallet and you will find smart chips and a magnetic stripe on each card. You may even have a hearing aid in your ear, or if you have heart problems a computer inside you, in a pacemaker. How many computers?

We are all cyborgs.

Box 3.4 The riddle of the Sphinx

The Sphinx asked passing travellers, ‘What creature walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at noon, and three legs in the evening, but is weakest when it has most legs’. Oedipus replies that the answer is a man, who crawls on all fours as an infant, two legs as an adult, and needs a walking stick when old.

The use of physical prostheses is, of course, not new; walking sticks have probably been around as long as people, and the first use of splints dates back to the fifth Egyptian Dynasty nearly 5000 years ago [Be09]. The core difference is that the new technologies are mainly information prostheses, helping us to think or communicate better. However, the two have been coming together with increasingly sophisticated medical prosthetics that use digital technology to sample tiny muscle movements or nerve signals and use these to control robotic limbs.

In gaming, head-mounted displays in eye glasses are becoming common. For ‘serious’ mobile computing these offer the potential to create virtual screens far larger than can be accommodated on a phone. These displays can now be almost indistinguishable from ordinary glasses. However, discreet cyborg technology can have its own problems.

Some years ago Jennifer Sheridan studied users of wearable technology at Georgia Tech. Because the display in the eye glass was only visible to the cyborg, the cyborg could be talking face-to-face with someone while simultaneously browsing web pages, reading email, or even carrying out a parallel instant messaging conversation. Sometimes this was simply rudeness, but often the virtual interactions were connected in some way to the face-to-face dialogue, just as one might look up a web page about a topic while talking to a friend. Sheridan found that the cyborgs had developed various ways to manage potential conflicts. They might say something like ‘hold on while I check that’ before focusing on the web page or email. One cyborg had his head-mounted display arranged so that he had to look upwards at the ‘screen’, so it was obvious when he was not ‘there’ in the conversation as his eyes gazed heavenward.

Sheridan became interested in these three-way interactions and as an exploration she and technology–art group .:thePooch:. developed a performance, ‘the schizophrenic cyborg’, at an arts event [SD04]. ‘Normal’ cyborgs are in the centre and in control of the three-way interactions, but the schizophrenic cyborg shattered this control. He wore a small display strapped to his waist and wandered round the exhibits at the event. Another performer, hidden up in a high gallery, provided the content of the display. The hidden performer could see from a distance but not hear what was going on. The hidden performer would display inviting comments, like ‘hug me’, ‘I’m lonely’, or make comments — ‘you in the red dress’.

When people came to talk to the cyborg they would not at first believe that it was not the cyborg himself controlling the display, and even when they did accept that it was a third person, they still interacted in ways that did not fully take into account the distinction. Some began to ignore the cyborg wearing the display and focus on the screen instead. We normally expect a single area of space to hold just one person. The participants were faced with a single space that in a sense ‘held’ two people, the cyborg himself and the hidden performer. In self-reports later, the cyborg repeatedly used language that alternated between first and third person accounts of himself, suggesting that it was equally confusing to experience someone else apparently occupying the same space as oneself.

On an even more intimate level, while people with a pacemaker or internal insulin pump have these implanted for medical reasons and would undoubtedly choose to have them removed were it medically safe to do so, there are those who choose to have computers permanently implanted in their bodies.

Various artists, notably Stelarc, an Australian-born performance artist, have explored the relationships between technology and the body: ingesting devices, strapping them to their bodies or in various ways insinuating metal into flesh. In one performance Stelarc had electrodes strapped to his skin so that they stimulated the muscles of his arm [ST09]. Measurements of network activity were used to drive the electrodes, so that people could use computers across the Internet to make his arm jerk and move without his control.

Kevin Warwick, Professor of Cybernetics at the University of Reading, believes that the embedding of digital technology into our bodies is a next inevitable step, and that before long we will all do this through choice [Wa03]. Putting this into action, he has had various implants including one that linked nerves in his arm to those of his wife. While he was away on an overseas trip they could feel each other’s movements (but only when the device was turned on!).

It may seem unlikely that people would willing do this outside an academic experiment, but in fact it is already happening. In Glasgow, Barcelona and Rotterdam nightclub goers can have a small chip implanted that allows them to enter quickly and to pay for drinks without having to carry money [Ma05]. Compared to this, Steve Mann’s cyborg technology begins to look mundane!

References

1. [Be09] Mary Bellis (2009), The History of Prosthetics. about.com, (accessed June, 2009) http://inventors.about.com/library/inventors/blprosthetic.htm [3.6]

2. [DG10] Alan Dix, Steve Gill, Devina Ramduny-Ellis and Jo Hare (2010) Design and Physicality — Towards an Understanding of Physicality in Design and Use. In: Designing for the 21st Century: Interdisciplinary Methods and Findings. Designing for the 21st Century, part 2. Gower, London, pp. 172-189. ISBN 9781409402404 [3.4]

3. [Gr12] Andy Greenberg (2012). McDonald’s Staff Denies ‘Physical Altercation’ With Cyborg Scientist. Forbes, dated 18 July 2012. accessed 9/1/2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/andygreenberg/2012/07/18/mcdonalds-staff-denies-physical-altercation-with-cyborg-scientist/#34c2ed204c89 [3.6]

4. [HO09] Home Office. The national DNA database. (accessed June 2009) http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/science-research/using-science/dna-database/ [3.5]

5. [Ja57] Wojciech Jastrzębowski (1857). An outline of ergonomics, or The science of work based upon the truths drawn from the Science of Nature. Translation: Danuta Koradecka (ed.), Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa (tr.). Warsaw : Central Institute for Labour Protection, 2000. [3.4]

6. [JS15] Joshi, V. and Srinivasan, M. (2015). Walking on a moving surface: energy-optimal walking motions on a shaky bridge and a shaking treadmill can reduce energy costs below normal. Proceedings. Mathematical, physical, and engineering sciences, 471(2174), 20140662. [3.2]

7. [Man12] Steve Mann (2012). Physical assault by McDonald’s for wearing Digital Eye Glass. dated 10 Oct 2010, accessed 9/1/2019. http://eyetap.blogspot.com/2012/10/mcveillance-mcdonaldized-surveillance.html [3.6]

8. [MP99] Nicolas Marmaras, George Poulakakis, Vasilis Papakostopoulos, Ergonomic design in ancient Greece, Applied Ergonomics, Volume 30, Issue 4, 1999, Pages 361-368, ISSN 0003-6870, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0003-6870(98)00050-7. [3.4]

9. [Ma05] Lorna Martin. This chip makes sure you always buy your round. The Observer, Sunday 16 January 2005. http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2005/jan/16/theobserver.theobserversuknewspages [3.6]

10. [SD04] Sheridan, J.G., Dix, A., Bayliss, A., Lock, S., Phillips, P., Kember, S. Understanding Interaction in Ubiquitous Guerrilla Performances in Playful Arenas. Proceedings of British HCI 2004, September 6-10, Leeds, UK [3.6]

11. [ST09] STELARC (official website), accessed March 2009. http://www.stelarc.va.com.au/ [3.6]

12. [SA05] Strogatz, S, Abrams, D., McRobie, A., Eckhardt, B. and Ott, E. (2005). Crowd synchrony on the Millennium Bridge. Nature, 438:43, DOI:10.1038/438043a [3.2]

13. [Wa03] Warwick, K. (2003). A study in cyborgs. Ingenia – Issue 16, Jul 2003. The Royal Academy of Engineering. pp.15-22 [3.6]